A quiet shift in dementia science is gathering pace, with lab results hinting at a fresh route to protect fading memories.

A team working across China and Spain has tested a way to clear toxic brain build-up without forcing drugs past the brain’s defences. Their method nudges the body’s own clearance machinery, and early signals in mice look striking.

What the researchers did

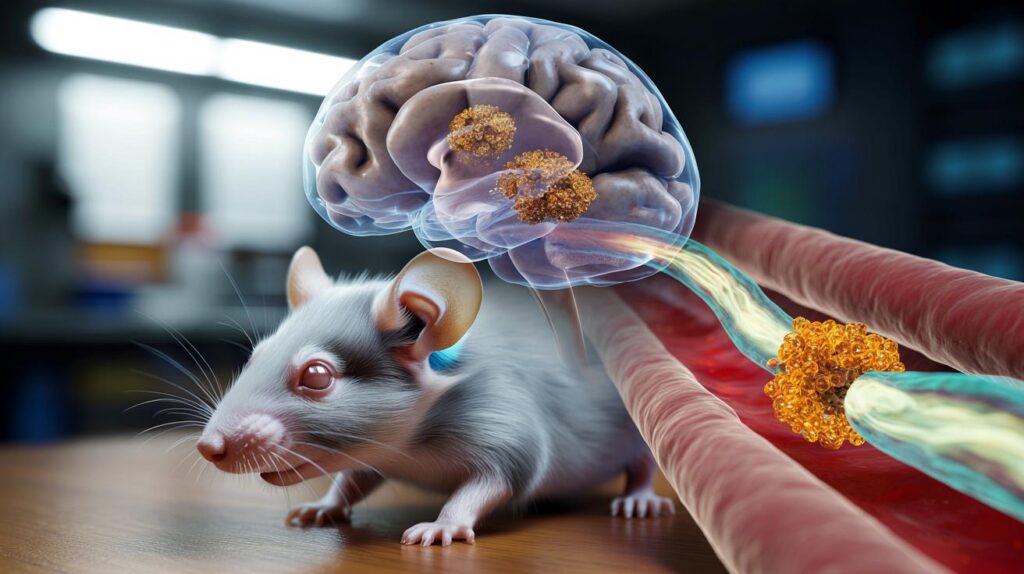

Instead of trying to push medicines into the brain, the scientists designed tiny nanoparticles that dock at a protein gatekeeper called LRP1 on the blood–brain barrier. LRP1 helps shuttle molecules and waste out of the brain. By targeting this transport route, the team triggered the removal of amyloid, a sticky protein that gathers into plaques in Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers report that engaging LRP1 on the blood–brain barrier set off a natural clearance pathway that flushed amyloid from the brain.

The work, published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, describes a “therapeutic strategy” that steers nanoparticles to the blood–brain barrier rather than deep into brain tissue. The approach aims to restore the barrier’s protective function and improve waste disposal, both of which can falter in Alzheimer’s.

Why the blood–brain barrier matters

The blood–brain barrier acts like a finely tuned filter. It keeps harmful agents out while letting vital nutrients through. In Alzheimer’s, this barrier can become leaky or sluggish, and transport proteins such as LRP1 may work less efficiently. That can leave amyloid and other toxins lingering longer than they should.

Repairing or rebalancing this interface could help several disease processes at once: inflammation, impaired blood flow and protein build-up. It also sidesteps a long-standing obstacle in neurology—drug delivery—by harnessing a system the brain already uses.

What the results really show

In mouse models of Alzheimer’s, the nanoparticle strategy did not merely shift lab readings. It produced behavioural changes measured in cognitive tests.

- Amyloid burden fell by nearly 45% after treatment.

- Spatial learning and memory improved to levels seen in healthy “wild-type” mice.

- Benefits persisted for up to six months in the study animals.

- The intervention targeted LRP1 on the blood–brain barrier using nanoparticles.

- The design activated an export pathway rather than forcing drug entry into the brain.

Nearly 45% less amyloid, memory scores comparable to healthy mice, and effects lasting as long as six months were reported in early experiments.

These signals matter because they link biological change to functional outcomes. Lower plaque counts aligned with cleaner performance in mazes and memory tasks, suggesting benefits extend beyond lab slides.

What experts are saying

UK scientists welcomed the ingenuity but urged restraint. Alzheimer’s Research UK called the findings a valuable addition to evidence that fixing the blood–brain barrier could help human disease, while stressing it remains early-stage mouse work. Independent academics noted the novelty of reprogramming an export pathway rather than forcing drug entry and flagged the need for replication.

The message from across the field is consistent: promising biology, careful optimism, and a demand for larger, independent studies to check the effect lasts and remains safe.

How this compares with today’s tools

Several therapies under investigation act directly on amyloid inside the brain, often by binding the protein so immune cells can remove it. Those approaches can face delivery hurdles and side effects linked to blood–brain barrier stress. The LRP1 strategy proposes a different angle: amplify the brain’s waste removal instead of adding more cargo to an already congested system.

| Approach | Main target | How it works | Key limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-based amyloid clearance | Amyloid deposits in brain tissue | Tags amyloid for immune removal | Delivery across blood–brain barrier and inflammatory risks |

| LRP1-targeted nanoparticle strategy | Blood–brain barrier transport protein (LRP1) | Reactivates natural export of amyloid | Evidence confined to mice; human translation unknown |

What happens next

Moving from mice to people brings hard questions. Doses that suit small animals might not scale. Human LRP1 biology and barrier function vary with age, genetics and vascular health. Long-term activation of a transport pathway could shift other molecules unexpectedly. Regulators will expect extensive toxicology, careful monitoring for microbleeds, and proof that benefits outweigh risks in older adults who often take multiple medicines.

Before this approach reaches clinics, researchers must confirm safety, reproducibility and durable benefit in larger, independent studies and, ultimately, in humans.

Signals of progress and gaps to close

What looks encouraging

Targeting the blood–brain barrier gives researchers a way to influence disease upstream, where waste removal falters. The alignment between a sizeable drop in amyloid and stronger performance in cognitive tasks points to a mechanism that affects behaviour, not just biomarkers.

What remains uncertain

Mouse models capture slices of Alzheimer’s biology, not the full human condition. People live with mixed pathologies, including tau tangles, vascular damage and inflammation. A single pathway may not address all of these. Manufacturing consistent nanoparticles at clinical scale and confirming precise brain delivery also pose engineering challenges.

Why it matters to you and your family

More than a million people in the UK live with dementia, most with Alzheimer’s disease. New directions are badly needed, and a line of research that reduces amyloid by almost half and sustains gains for six months in animals deserves attention. No one should treat this as a cure, and no one can say yet whether it will help people. But it widens the set of strategies that could be combined in the future—drugs, lifestyle interventions and vascular care—to slow decline.

Practical context and next steps for readers

While scientists refine barrier-targeted treatments, you can act on factors that affect brain and vessel health. Managing blood pressure, keeping active, sleeping well and treating hearing loss each reduces dementia risk over time. These steps also support the very systems—the vessels and barrier—that approaches like LRP1 targeting seek to stabilise.

For families considering research participation, memory clinics and registries run screening programmes for trials. Ask about studies focused on blood–brain barrier function or amyloid clearance. If a trial lists LRP1 or nanoparticle transport, check for robust safety monitoring, clear dose-escalation plans and cognitive measures that track daily functioning, not just lab biomarkers.

Key terms to know

- Blood–brain barrier (BBB): a selective interface that regulates what enters and exits the brain from the bloodstream.

- LRP1: a transport protein on BBB cells involved in shuttling molecules and clearing waste including amyloid.

- Amyloid: a protein fragment that accumulates into plaques around brain cells in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Nanoparticle: an engineered particle measured in billionths of a metre, designed here to interact with BBB transport.

45% amyloid drop and six months of better memory in mice is huge. The BBB angle via LRP1 feels fresh—nudging clearance instead of shoving drugs in. Any word on off-target cargo geting swept out too, or microbleed risks?

So we’re basically unclogging the brain’s drain rather than pouring more cleaner into it—love the plumbing vibes 😀 Do age-related declines in LRP1 expression blunt this effect? Also, could essential peptides get flushed faster? And how gnarly is scaling nanoparticle manufacturing with consistent surface chemistry?