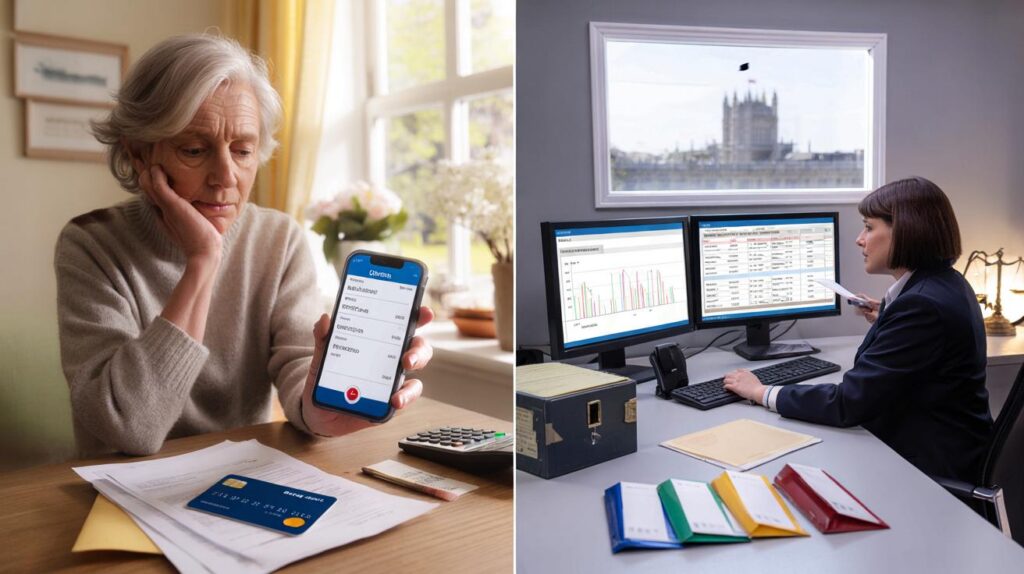

Millions on benefits face a new wave of checks as ministers tighten rules and banks prepare for tighter scrutiny across accounts.

The government plans a new regime to curb fraud and errors, with banks expected to monitor accounts and flag potential risks. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) says a person will review every alert and that the system won’t assume guilt.

What is changing and when

The Public Authorities (Fraud, Error and Recovery) Bill will empower the DWP to require banks to monitor for signs of welfare fraud and error. Ministers intend to start bank checks from April 2026, subject to the Bill clearing Parliament and detailed regulations being laid.

Bank monitoring for benefits will begin from April 2026, with checks designed to spot risk signals rather than prove wrongdoing.

The Bill sits within a wider savings drive announced at the Budget and Spring Statement. Ministers forecast £1.5bn in recovered losses over five years, contributing to a broader £9.6bn target by 2030.

Who will be targeted first

Experts expect the early focus to fall on three benefits where eligibility depends on income and savings, and where error and fraud rates have historically been higher.

- Universal credit (UC)

- Pension credit

- Employment and support allowance (ESA)

Officials say the new powers won’t give blanket access to everyone’s bank statements. Instead, banks will check for indicators set out in law and pass limited information to the DWP when an account meets those criteria. A caseworker will then review the signal in full, with the department stressing it does not work on a presumption of guilt.

What banks will look for

The legislation enables eligibility checks and bank account surveillance intended to identify risk, such as discrepancies that could suggest undeclared capital or income. The DWP has stated that alerts from banks are not generated by its own algorithms and that staff will assess each case before any action.

Signals of potential fraud or error will trigger a human review, not an automated decision, according to the DWP.

New powers and penalties

The Bill introduces civil penalties as an alternative to prosecution in some cases, with ministers arguing fines deter fraud while speeding up recovery of public money. The department says there will be “robust” oversight and reporting rules, and staff training to high standards.

The politics and the numbers

Peers in the House of Lords are due to scrutinise the Bill in mid and late October, a key step before detailed regulations can be drafted. Campaigners including Disability Rights UK, Age UK, Privacy International, Child Poverty Action Group and Big Brother Watch have raised alarms about “suspicionless” mass checks and the risk of a Horizon-style IT failure leading to false accusations.

Campaign groups warn of privacy risks and wrongful flags; ministers insist on proportional checks, oversight and clear accountability.

| Key point | Detail |

|---|---|

| Planned start | From April 2026 |

| Legislation | Public Authorities (Fraud, Error and Recovery) Bill |

| First benefits in scope | Universal credit, pension credit, ESA |

| Projected savings | £1.5bn over five years |

| Wider fiscal aim | £9.6bn by 2030 |

| Parliamentary scrutiny | House of Lords sessions on 15 and 21 October |

What this means for you right now

If you receive UC, pension credit or ESA, the core rules do not change before April 2026. But the checks to enforce those rules will tighten. Keeping your information accurate and up to date will matter more as banks begin flagging risks to the DWP.

- Report changes quickly, including new work, extra income, savings changes or a new partner moving in.

- Keep records: payslips, bank statements, letters about inheritances or one-off payments make it easier to explain a spike in your balance.

- Know the capital rules: UC reduces awards where savings exceed £6,000 and normally stops when savings reach £16,000.

- Check your benefit journal for DWP messages and respond within the stated time limits.

If you are wrongly flagged

You can ask the DWP for an explanation of any decision and challenge it through mandatory reconsideration, then appeal to a tribunal if needed. Keep copies of statements and correspondence that show why your account activity is legitimate. Independent advice bodies can help you prepare evidence and meet deadlines.

Why campaigners are worried

Rights groups fear “suspicionless” monitoring could chill trust in the welfare system and sweep in law-abiding claimants—especially pensioners, disabled people and carers. They draw a parallel with the Post Office Horizon scandal, where flawed data drove wrongful prosecutions and financial ruin.

Ministers reject that comparison. They argue the bank checks target risk, not individuals, and that human caseworkers—not algorithms—will make decisions. The department also promises transparency through oversight and reporting requirements written into the Bill.

Practical examples to consider

A UC claimant who receives a one-off insurance payout may see their balance jump. If that money pushes savings over £6,000, their award can fall; over £16,000, UC usually stops. Declaring the payment, explaining its source and, if relevant, showing how it will be used can prevent a misunderstanding when bank checks begin.

Someone on pension credit who opens a new account for a relative’s shared expenses should note the arrangement and keep receipts. Mixed funds can create awkward questions if a bank flag appears later. Clear records help a caseworker see what belongs to whom.

What to expect next

As the Lords examine the Bill, expect amendments on oversight, data handling and redress for errors. Detailed regulations will set the final shape of bank monitoring. The DWP says it will train staff and publish guidance before April 2026 so claimants and banks know exactly how the system will work.

If you manage your money carefully and report changes promptly, you reduce the risk of an overpayment or a civil penalty once the new checks go live. Keeping a simple folder of statements and letters now can save time when questions arise.

Can someone clarify what “risk signals” actually are? If my balance jumps because of a refunded deposit or a one‑off gift, does that trigger an alert, and how do I prove it’s legitimate without handing over my entire banking history? Also, will we be told when a check is run?

So if I buy a second-hand sofa with cash, does the DWP think I’m a secret millionaire? Asking for a friend.