A rush of hope in a lab that smells faintly of ethanol and warm plastic: Swedish researchers say they’ve found a bacterium that tears through PET — the stuff of bottles and polyester — in record time. Not in years. Not in weeks. Fast enough to make recycling feel alive again.

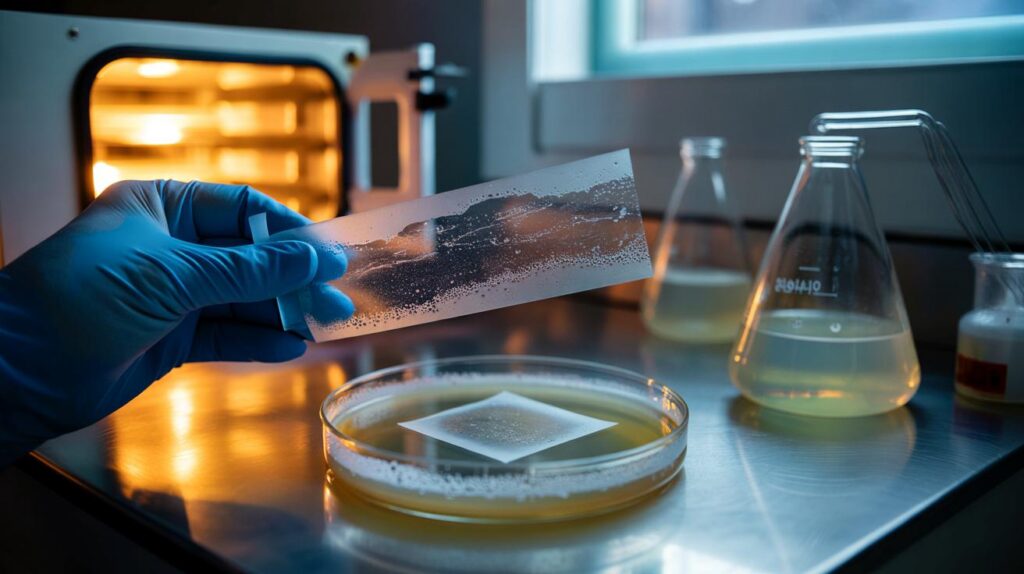

The incubator door opens with a soft sigh and a gust of heat, and someone’s timer pings like a microwave at 2 a.m. It’s late in Gothenburg, but the petri dishes look alert — milky halos spreading across thin films of PET. A graduate student holds a strip of bottle plastic up to the light, and it looks… thinner than an hour ago. Maybe it’s the angle. Maybe not.

I catch my breath and check the clock. One of the flasks has a faint chemical sweetness, a sign that monomers are leaching into the broth. In the corner, a whiteboard lists temperatures and pH tweaks in hurried scrawl. The team watch in that quiet way scientists watch when the improbable starts happening. Then something gives.

Inside the Swedish lab racing plastic’s stopwatch

The story begins far from the headlines, in soil samples and water scooped from the edges of a Scandinavian stream. The bacterium didn’t arrive with fanfare. It arrived in a jar, and then in a series of flasks, and then on a wafer-thin square of PET where it began to do what few microbes can do quickly: unmake a plastic humanity swore would last.

This is not just another plastic-eating headline. Under carefully tuned conditions — warm but not hot, gently shaken, pH steady as a metronome — the strain secretes enzymes that soften PET’s stubborn bonds. On a lab bench, that looks like fogging, then pitting, then the faintest lace of holes spreading across a window-clear film. The effect is part chemistry, part choreography, and it happens disarmingly fast.

Numbers tell a blunter tale. Close to one million plastic bottles are sold every minute worldwide, and studies suggest only a small fraction of all plastic ever made gets recycled. In one overnight test, a fragment from a drinks bottle came out of the incubator visibly perforated — not just grazed. The bacterium didn’t nibble; it chewed. Existing enzyme systems can work, but they often need more heat, tight pre-treatment, or time measured in days. The Swedish flasks suggest a different tempo.

What’s happening under the lid is classic depolymerisation with a twist. PET is a chain of repeating units that can be clipped back into their building blocks — terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol — if you wield the right molecular scissors. This microbe’s scissor set appears unusually sharp for PET, possibly thanks to a surface-binding domain that hugs the plastic and speeds up attack. It’s not magic, it’s kinetics: more contact, more cuts, clearer broth.

How to turn a microbe into a recycling workhorse

Scaling this up means thinking like a brewer. Shred the PET to increase surface area. Wash it to remove food residues, caps, and labels that slow enzymes down. Pre-warm the slurry, feed it into a stainless-steel bioreactor, set the temperature and pH where the bacterium feels at home, and keep the mix moving so fresh plastic meets fresh enzyme. Monitor the air, the foam, the smell. Harvest the monomers when the solution goes clear.

Real rubbish is messy. PET arrives mixed with dyes, multilayers, and the wrong polymers sneaking in like party crashers. The bacterium won’t touch PVC or PP, and coloured bottles may degrade differently from water-clear ones. That’s not failure, it’s process design. We’ve all had that moment when we rinse a yoghurt pot and wonder if it matters. Let’s be honest: nobody really does that every day. Sorting still matters, but better enzymes loosen the screws on perfectionism.

Speed is only half the story. The other half is integration: can you drop this into existing facilities without ripping out walls? The Swedes think in loops, not lines, reusing solvents, capturing heat, and feeding purified monomers back into new PET so it’s genuinely circular.

As I scanned the data, a simple thought landed: if plastic can be unmade locally, the world suddenly gets smaller and cleaner.

- Lower-temperature, faster depolymerisation cuts energy bills for recyclers.

- Cleaner monomers mean bottle-to-bottle recycling without quality loss.

- Regional micro-factories could shrink transport miles and emissions.

- Fewer additives and better sorting make everything hum.

What changes if PET can be unmade overnight?

The timeline in your head bends. A t-shirt stops being a dead end and becomes a temporary form. Cities imagine small-footprint plants swallowing bales of bottles and exhaling feedstock by morning. Manufacturers stop hedging quality and begin speccing recycled PET as a default, not a virtue signal. Investors smell an industrial upgrade, not a tidy moral gesture. And river clean-ups, those noble weekend slogs, start to feel like rescues and refuels, not dumpsters on water.

There’s a check on the euphoria. PET is just one polymer in a mixed, noisy world. The bacterium does its best work when you set the table for it — heat right, pH right, plastic ready. *The tech is only as circular as the systems we build around it.* But the psychological shift is real. Plastic stops being a forever-thing and turns into a temporary choice. That idea carries weight. It feels like breath held, then finally released.

| Key points | Details | Interest for reader |

|---|---|---|

| Swedish team isolates a PET-degrading bacterium | Works at moderate temperatures, accelerates PET depolymerisation under lab conditions | Signals faster, cleaner bottle-to-bottle recycling |

| Record-time breakdown in tests | Visible perforation and monomer release in hours-to-overnight scenarios | Hints at future facilities that unmake plastic on a daily cycle |

| Path to real-world adoption | Shredding, pre-treatment, bioreactors, closed-loop monomer recovery | What it would take for your bottles and clothes to return as new |

FAQ :

- Is this bacterium safe to use at scale?In industrial setups, microbes live in closed vessels and are sterilised after runs. The aim is to keep them busy, contained, and useful — not roaming beyond the plant.

- Does it eat all plastics or just PET?Just PET. That’s a feature, not a bug. Precision helps recover pure monomers for high-quality recycling without cross-contamination.

- Will it work on ocean plastic or dirty waste?Heavily weathered or contaminated PET can still be processed, but it often needs washing and shredding to restore surface area and remove grime that blocks enzymes.

- When could this hit a recycling plant near me?Pilots typically run for months to a couple of years. If the Swedish data holds in larger reactors, early adopters could bolt on bioprocess lines sooner than you think.

- Does breaking down PET create microplastics?No. The goal is chemical depolymerisation to liquid monomers, not grinding into smaller solids. When the process works, the plastic dissolves into its building blocks.

If this truly chews through PET overnight, that’s a step-change, not a tweak. If the monomers are clean enough for bottle-to-bottle at scale, we’re talking real circularity instead of green PR. Please keep publishing data, especially side-by-sides with current enzyme systems.

“Record time” compared to what baseline exactly—hours vs. days? Also, how defintely does it handle dyes and multilayers in municpal waste streams? Lab wins are great, but the curbside mix is a beast.