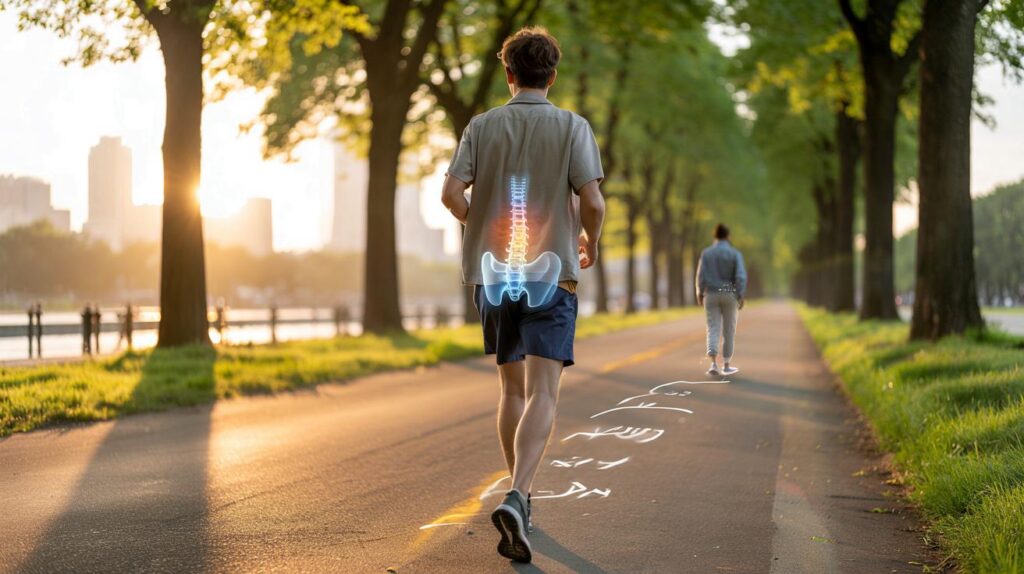

Back pain haunts busy lives, yet a simple change to your routine could ease pressure on your spine and wallet.

A large Norwegian analysis now points to a clear, practical fix for everyday backs: spend more minutes on your feet. The researchers say time on the move, not speed, is what shifts the dial on future lower back problems.

Why a longer daily walk matters

Lower back pain disrupts work, sleep and family life. It affects hundreds of millions worldwide and often returns after short-lived relief. Fresh evidence suggests that adding up your gentle walking minutes across the day can reduce the odds of persistent trouble.

Researchers report that people who rack up more than 100 minutes of walking per day face a 23% lower risk of long-term lower back problems than those who manage 78 minutes or less.

That number challenges the idea that only fast, sweaty sessions deliver protection. Slow, steady movement appears to help the spine, hips and core muscles do their jobs, without the jarring loads that running sometimes brings.

What the study actually measured

The data come from more than 11,000 adults in the Trøndelag region of Norway. Participants wore small sensors on their thighs and backs for a full week, capturing real-life movement instead of relying on memory. This approach reveals how much people actually walk, sit and stand in a typical day.

Researchers compared daily walking time with the likelihood of reporting lasting lower back problems. They found a clear pattern: the more minutes walked, the lower the risk. Intensity still mattered, but the total time on the move had the stronger link.

The volume of walking mattered more than the pace. Minutes, not miles per hour, were the standout factor.

How much time to bank each day

Think of your walking like a savings pot. Each short trip adds up. The threshold linked with benefit was just over 100 minutes per day, spread however you like.

| Daily walking time | Indicative risk versus baseline | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 78 minutes or less | Baseline risk | Reference group in the analysis |

| 79–100 minutes | Not specified | Transitional range; aim higher if you can |

| More than 100 minutes | About 23% lower risk | Based on sensor-measured activity over one week |

What about intensity and intervals

Interval walking and high-intensity training have their place, and many people enjoy them. This study suggests you do not need speed to protect your back. If brisk walking suits you, keep it. If not, slower strolls still count. The shared goal is more total minutes.

Regular movement increases blood flow to spinal structures and loosens stiff joints. Walking engages the glutes and deep core muscles that stabilise the lumbar spine. Gentle repetition may also reduce pain sensitivity over time.

Who stands to benefit most

Anyone can develop back pain, with risks rising from around 30 years of age. Extra risk tends to cluster in people who carry excess weight, smoke, rarely exercise, or live with conditions such as osteoporosis, arthritis and some cancers. For many, low-impact activities like walking, cycling and swimming provide a safer way to build strength without jolting the spine.

In the United States, nearly 65 million adults report a recent episode of back pain, and around 16 million say it limits daily life. The economic toll runs into billions each year through healthcare costs and lost work. A simple, low-cost habit that nudges risk down is attractive for households and health systems alike.

Practical ways to reach 100 minutes

Breaking the target into smaller chunks makes it easier to sustain. Ten minutes here, fifteen there, and the total grows almost without effort.

- Get off the bus, tram or Tube one stop earlier both ways.

- Walk phone calls with friends or family; pace indoors if the weather turns.

- Build a short loop into lunch, and another after dinner.

- Run errands on foot for items that fit in a small bag or backpack.

- Use stairs where practical; add a two-minute lap before you sit back down.

- Set a gentle reminder every hour to stand, stretch and walk for two minutes.

- Wear supportive, comfortable trainers to reduce strain on feet and lower back.

Signals to watch—and when to seek help

Mild soreness that eases as you warm up is common when you increase activity. Slow down if sharp pain appears. Stop and speak to a clinician if you notice leg weakness, numbness, changes in bladder or bowel control, or night pain that does not settle. People with diagnosed spinal conditions should discuss any new programme with their healthcare professional.

Small changes that stack up

Consider a simple weekly plan. Aim for five days with two or three short walks each, and top up at the weekend with a longer, scenic stroll. A park route or a lap around the block counts the same as a treadmill. Keep a note on your phone: minutes done, minutes to go.

Variety helps motivation. Alternate quiet, mindful walks with socially engaging ones. Add gentle mobility drills at the end: knee-to-chest, hip circles, and a few seconds of wall-supported calf raises. These moves support the same muscle groups that walking strengthens.

What this means for your day

Think of walking minutes as a daily staple, like brushing your teeth. The evidence shows that simply increasing time on your feet may reduce the chance of long-term lower back trouble. You do not need to chase a pace. You do need to show up, little and often, until your day holds those 100-plus minutes.

Add minutes, not pressure. Spread gentle walks across the day, and let consistent movement protect your back.

A quick starter plan you can use today

- Morning: 15 minutes to the shop or around the block.

- Midday: 20 minutes after lunch to boost energy for the afternoon.

- Afternoon: 10 minutes between meetings or chores.

- Evening: 30–40 minutes with music, a podcast or a companion.

That schedule crosses the 100-minute line without a single hard effort. Adjust the blocks to suit your routine, weather and mood. Keep it gentle, consistent and comfortable. Your spine, and your future self, will thank you.

Love the “minutes over pace” message—feels actually doable. I started adding 10–15 minute strolls between tasks and my back feels less stiff already. Thanks for breaking it down so clearly!

Cool, but how much of that 23% is causation vs. active people just being healthier overall? Did the sensors and analysys control for BMI, smoking, or prior back isues?