In clinics across Europe, older adults tried a new way to sharpen fading sight. It involved a wafer-thin chip and smart glasses.

What the trial shows

Researchers writing in the New England Journal of Medicine report early but striking results from an international study of an electronic retinal implant for people with age-related macular degeneration. The team enrolled 38 participants, average age roughly 79, who lived with advanced dry AMD. After implant surgery and months of rehabilitation, 8 in 10 participants recorded clinically meaningful improvements one year on. Those gains did not restore perfect eyesight, yet they moved the needle on reading, navigating rooms and spotting high-contrast objects.

80% of 38 older patients with advanced dry AMD improved their vision a year after receiving an implant and training.

Why this matters for millions

Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of vision loss in older adults. The disease harms the central retina, eroding detailed sight used for reading and facial recognition. Global estimates suggest roughly 200 million people live with AMD. Risk climbs steeply with age. Data show about 2% of people aged 40–44 have AMD, rising to 42% in their late eighties and 60% in their late nineties. Most cases are the “dry” type, which often progresses slowly, while “wet” AMD tends to cause faster damage but has more established treatments. The trial focused only on dry AMD, where unmet need is substantial.

How the bionic vision works

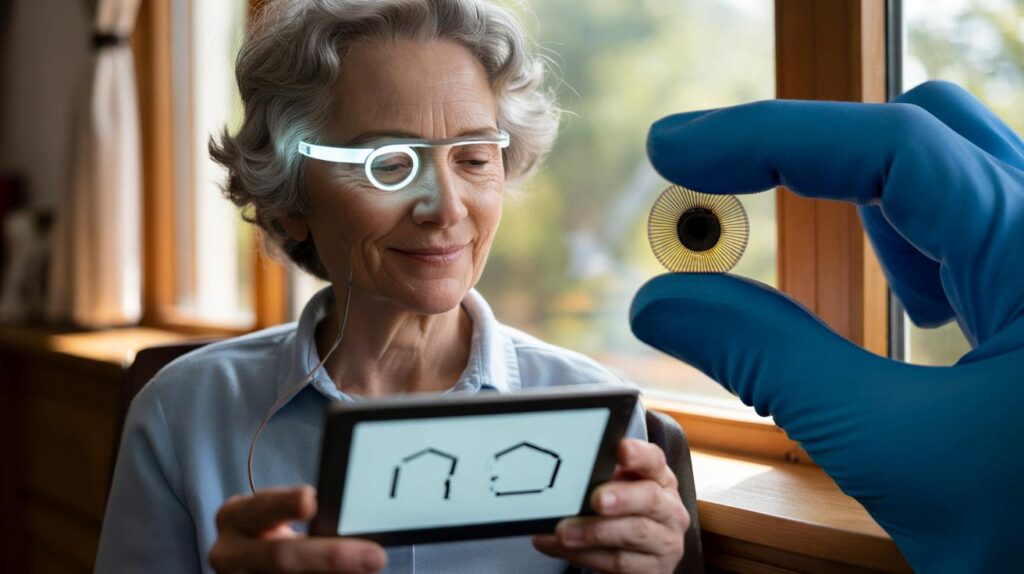

The surgical team placed a tiny, light-sensitive implant beneath the retina. The device is roughly half the thickness of a human hair. It sits in the central macula, where photoreceptors have dwindled. Unlike earlier wired implants, this system uses a custom pair of augmented reality glasses connected to a small waist-worn computer. The glasses capture a live video feed. They then project near‑infrared patterns onto the implant. The implant converts that light into electrical signals that stimulate remaining retinal cells, which send information along the optic nerve to the brain.

The implant sits under the retina and is driven by infrared images from smart glasses, turning light into nerve signals.

Training turned signals into sight

Participants did not leave theatre seeing magically. They trained for months with specialists to interpret the new signals. Sessions focused on letter recognition, edge detection and scanning techniques, much like learning to read a new code. As practice accumulated, many participants reported faster reading speeds and easier navigation in unfamiliar spaces. The system currently renders images in black and white. The research team plans software upgrades to improve grey-scale contrast, which could help with face recognition.

Numbers at a glance

| Measure | Value |

|---|---|

| Participants | 38 |

| Average age | ~79 years |

| Sites and countries | 17 sites across 5 European countries |

| Follow-up | 12 months |

| Clinically meaningful improvement | 80% of participants |

| Image colour | Black and white (grey-scale enhancement in development) |

Expert reactions and caution

Retina specialists praised the engineering leap. They also urged careful interpretation. Motivation after receiving a cutting‑edge device can boost performance. So can intensive rehabilitation. Critics would like a control group receiving the glasses and training, but no implant, to isolate the device’s effect. Larger, longer trials with such controls would tighten the evidence and help regulators weigh real‑world benefits.

Without a control group, training effects can inflate test scores. The next trial needs a rigorous comparator.

Targets for the next generation

Several researchers involved in the project say the current system will not deliver 20/20 vision on its own. They aim to lift many participants past the threshold for legal blindness, with better face and emotion recognition as a practical goal. Two priorities stand out: stronger grey‑scale processing and higher resolution in the implant array. Early animal work suggests higher‑density arrays could be feasible, but those designs must prove safe and reliable in people.

What this could mean for you

If you or a family member lives with advanced dry AMD, this technology signals a path to functional improvements rather than perfection. The reported gains include reading larger print, identifying high‑contrast obstacles and finding door frames more quickly. For many, that translates to greater independence.

- Expect a surgical day case with local or general anaesthesia, followed by check‑ups.

- Plan for weeks to months of visual rehabilitation with a specialist team.

- Wear the glasses and waist unit daily; battery life and comfort matter in real use.

- Anticipate black‑and‑white vision now, with possible software upgrades later.

- Set goals around tasks: reading menus, recognising faces at close range, moving safely at home.

Risks, access and costs

Any eye surgery carries risks, including infection, retinal detachment and inflammation. The surgical teams in this trial reported acceptable safety so far, but larger studies will test consistency across centres. Access will depend on regulatory review in the regions where the study ran and on reimbursement decisions by health systems. The hardware involves an implant, camera glasses and a body‑worn processor, plus specialist rehabilitation. That package suggests a significant price at launch, balanced against potential reductions in care needs and falls. Realistic cost‑effectiveness data will emerge only after broader deployment.

Dry versus wet AMD: why the focus matters

Dry AMD leaves patches of surviving photoreceptors. The implant leverages those pathways. Wet AMD follows a different biology, driven by abnormal blood vessels that leak. Many people with wet AMD receive injections that slow damage. The new implant is not designed to replace those injections. It targets people with dry disease whose central vision has eroded and for whom standard care offers little.

How clinicians may select candidates

Ophthalmologists will likely look for patients with stable retinal structure, sufficient residual pathways for stimulation and the capacity to commit to rehabilitation. Cognitive screening, dexterity to handle the kit and home support may all influence outcomes. Expect centres to build pre‑operative assessments that include contrast sensitivity, fixation stability and mobility goals.

The best results will likely come from the right patient, the right implant placement and relentless rehabilitation.

Tips to protect remaining vision while you wait

The implant sits within a broader care plan. People with AMD may benefit from low‑vision aids such as high‑contrast reading lamps, electronic magnifiers and bold‑print settings on tablets. An Amsler grid can help monitor sudden changes that need urgent review. Smoking cessation, balanced diet and regular eye checks remain core advice. None of these replace medical treatment, but they help preserve function day to day.

What to watch over the next 12–24 months

Look for a trial with a control arm to separate training effects from device effects. Watch for software updates that sharpen grey scales and stabilise latency, since lag can cause nausea and reduce reading speed. Keep an eye on durability: engineers need implants that hold their function over several years without extra surgery. If those pieces fall into place, hospitals could pilot the system in select clinics before broader adoption.

For readers managing AMD in the family, speak with a retinal specialist about eligibility for upcoming studies and the realities of rehabilitation. Ask how to combine the implant with low‑vision strategies you already use. A clear plan for training at home, including daily targets and simple logs, can turn early gains into lasting improvements.

80% of 38 people seeing meaningful gains at ~79 is incredible—functional reading and navigation after a year? This could give my dad some independence back 🙂