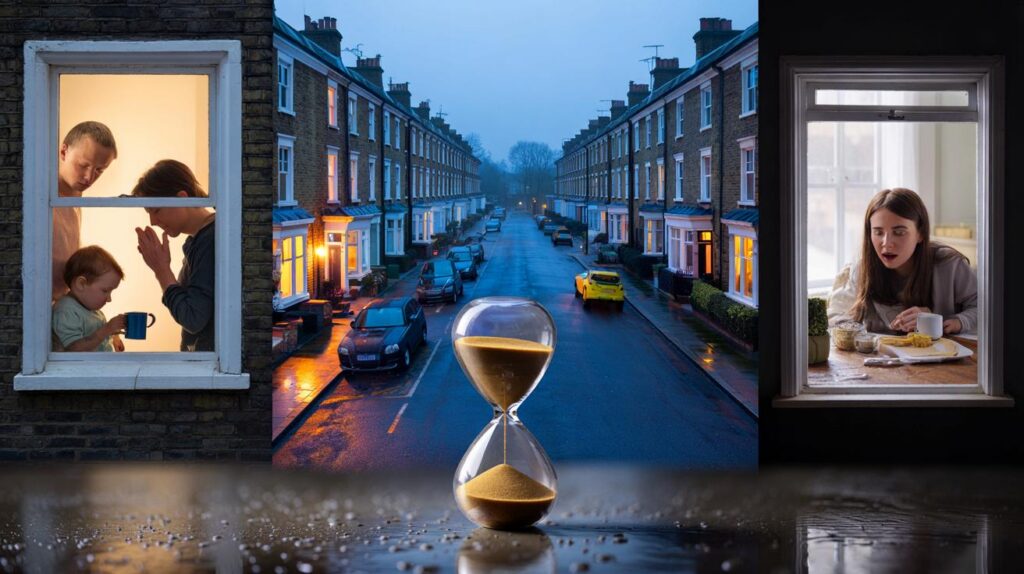

As the clocks shift, millions feel off‑kilter, reaching for extra coffee and wondering why a single hour bites so hard.

The 60‑minute jump between BST and GMT tinkers with more than your diary. It nudges hormones, appetite, mood and reaction time.

Why a single hour rattles your body clock

Your brain runs a daily programme that anchors sleep, hunger, temperature and alertness to light. Scientists call it the circadian rhythm. It prefers a stable 24‑hour pattern. Move the dial by 60 minutes and you create a one‑time‑zone mini jet lag. Most people adjust in three to seven days. Some need longer.

Light hits specialised cells in the eye and signals the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the master clock. That signal suppresses melatonin, raises cortisol at daybreak and times your energy peaks. Evening bright light does the opposite and delays sleep. Shift these signals and the whole system staggers.

Think of the clock change as a one‑zone jet lag: the body can realign by roughly 15–30 minutes per day with the right light.

Light, melatonin and the morning reset

Morning light advances the clock. A brisk walk outdoors after waking can move your internal rhythm earlier by up to half an hour per day. On dark mornings, rooms lit to 1,000–2,000 lux help. Phone screens reach only a fraction of that. Dim light in the last hour before bed allows melatonin to rise and sleep pressure to build.

Meals, movement and temperature cues

Your body also reads meals, activity and temperature as time cues. Regular breakfast anchors metabolism. A short burst of exercise raises core temperature and sharpens attention. Heavy late meals push digestion into the night and sabotage deep sleep. Keep evenings warm and calm; keep mornings bright and active.

The seven‑day fog: what most people report

Surveys in sleep clinics and workplaces paint a consistent picture in the first week after the switch.

- Shorter total sleep across the first two nights, typically 30–60 minutes.

- Fragmented sleep with early waking or difficulty dropping off, especially after the autumn change.

- Mid‑afternoon dips in focus, slower reaction times and small memory slips.

- Increased appetite for sweet or starchy foods, driven by clock‑metabolism mismatch.

- Lower mood, irritability and a sense of being “out of sync”.

Transport and safety researchers report shifts in accident patterns around clock changes. Some regions see a small rise in collisions after the spring transition when people lose sleep. Patterns vary by light levels, commuting times and latitude, so the risk isn’t uniform across the UK.

Performance drops first before sleep habits settle: plan critical tasks for late morning, not dawn, during the changeover week.

Children and older adults feel the swing first

Young brains and ageing brains like routine. They resist sudden clock moves and often show stronger effects.

| Group | Typical effect | Time to recalibrate |

|---|---|---|

| Pre‑school children | Bedtime battles, early waking, daytime tantrums | 3–7 days |

| Teenagers | Late sleep onset, morning sleepiness, missed breakfast | Up to 10 days |

| Older adults | Lighter sleep, disorientation on waking, steadiness issues | 5–10 days |

| Shift workers | Clock misalignment layered on shift pattern fatigue | Variable; often longer |

Patience and structure help. Keep wake‑up times steady, add daylight at breakfast and use calm pre‑bed routines. These simple anchors cut the wobble for both ends of the age span.

What to do this week

You can blunt the impact with small, specific changes. Start three to five days before the switch if possible. If not, begin today.

- Shift sleep by 15 minutes per day towards the new time. Keep the same steps: lights down, wash, read, lights out.

- Get 20–30 minutes of outdoor light within an hour of waking. If it’s gloomy, sit by the brightest window for breakfast.

- Time caffeine before early afternoon. Caffeine lingers and delays sleep when taken late.

- Keep naps short and early. Ten to twenty minutes before 15:00 helps without stealing night sleep.

- Move daily. A brisk walk at lunch sharpens the afternoon and improves night‑time depth of sleep.

- Eat on the new schedule within two days. Keep dinner lighter and earlier to protect deep sleep.

- Reduce evening screen glare. Use warm light and low brightness for the last hour before bed.

- Mind the drive home. Fatigue slows reactions. Leave more space, especially on darker routes.

Morning light is medicine for the clock; late‑evening bright light is its disruptor. Treat them that way.

Does the seasonal switch still make sense?

Energy savings from clock changes look smaller than once hoped, and they vary with modern lighting and heating. Health and safety arguments now shape the debate. Many clinicians favour a stable, permanent time because steady light cues help sleep, mood and learning. The European Union discussed scrapping seasonal changes, yet member states have not moved together, so the twice‑yearly ritual remains for now. The UK has no confirmed plan to alter the current BST/GMT system.

Latitude matters. Northern areas gain little morning light in winter no matter the clock, so routines and light exposure carry more weight than the legal time. Households can still claim better mornings by front‑loading light and movement.

Extra context you can use

Seasonal low mood links closely to light. If you feel flat, try consistent morning light, brisk outdoor walks and a regular sleep window. If low mood persists or you spot a pattern each winter, speak to your GP. Targeted light therapy boxes that deliver bright, broad‑spectrum light at breakfast can help some people; seek medical advice if you have eye conditions or bipolar disorder.

Melatonin can shift the clock when taken at the correct time and dose. Timing matters far more than milligrams. Many people take it too late. In the UK, treat melatonin as a medicine and discuss timing with a clinician, especially if you take other drugs or manage sleep disorders.

Want a quick personal test? Track three markers for a week after the change: time you feel alert in the morning, when you get hungry for lunch, and when you naturally feel sleepy. If all three run late or early by at least 60 minutes, you’re not aligned. Use morning light, steady meals and 15‑minute bedtime shifts until those markers converge.

Parents can build a simple countdown. Four nights out, move bedtime by 15 minutes. Add a brighter breakfast table and a short walk to school. Keep homework and screens earlier. By the changeover day, most children slip into the new rhythm with fewer tears.

Small habits compound. A brighter breakfast, a walk at lunch, a gentle wind‑down and a realistic bedtime can return the missing 30–90 minutes of sleep by the end of the week and steady your mood as the darker months begin.

Isn’t this just confirmation bias? I feel fine after the switch—maybe we overblow it tbh.

So my crankiness and biscuit cravings are officially “circadian”? My family will be thrilled with this scientific excuse 😅